Prince Philip: An extraordinary man who led an extraordinary life

He outlived nearly everyone who knew him and might explain him.

And so we have been left with a two-dimensional portrait of the duke; salt-tongued and short-tempered, a man who told off-colour jokes and made politically incorrect remarks, an eccentric great-uncle who'd been around forever and towards whom most people felt affection - but who rather too often embarrassed himself and others in company.

With his death will come reassessment. Because Prince Philip was an extraordinary man who lived an extraordinary life; a life intimately connected with the sweeping changes of our turbulent 20th Century, a life of fascinating contrast and contradiction, of service and some degree of solitude. A complex, clever, eternally restless man.

His mother and father met at the funeral of Queen Victoria in 1901. At a time when all but four of Europe's nations were monarchies, his relatives were scattered through European royalty. Some royal houses were swept away by World War One; but the world into which Philip was born was still one where monarchies were the norm. His grandfather was the King of Greece; his great-aunt Ella was murdered along with the Russian tsar, by the Bolsheviks, at Ekaterinberg; his mother was a great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria.

His four older sisters would all marry Germans. While Philip fought for Britain in the Royal Navy, three of his sisters actively supported the Nazi cause; none would be invited to his wedding.

When peace came, and with it eventual economic recovery, Philip would throw himself into the construction of a better Britain, urging the country to adopt scientific methods, embracing the ideas of industrial design, planning, education and training. A decade before Harold Wilson talked of the "white heat of the technological revolution", Philip was urging modernity on the nation in speeches and interviews. And as the country and the world became richer and consumed ever more, Philip warned of the impact on the environment, well before it was even vaguely fashionable.

He was forged by the turmoil of his first decade and then moulded by his schooling. His early years were spent wandering, as his place of birth ejected him, his family disintegrated and he moved from country to country, none of them ever his own. When he was just a year old, he and his family were scooped up by a British destroyer from his home on the Greek island of Corfu after his father had been condemned to death. They were deposited in Italy. One of Philip's first international journeys was spent crawling around on the floor of the train from an Italian port city, "the grubby child on the desolate train pulling out of the Brindisi night," as his sister Sophia later described it.

In Paris, he lived in a house borrowed from a relative; but it was not destined to become a home. In just one year, while he was at boarding school in Britain, the mental health of his mother, Princess Alice, deteriorated and she went into an asylum; his father, Prince Andrew, went off to Monte Carlo to live with his mistress; and his four sisters married and went to live in Germany. In the space of 10 years he had gone from a prince of Greece to a wandering, homeless, and virtually penniless boy with no-one to care for him.

"I don't think anybody thinks I had a father," he once said. Andrew would die during the war. Philip went to Monte Carlo to pick up his father's possessions after the Germans had been driven from France; there was almost nothing left, just a couple of clothes brushes and some cuff-links.

By the time he went to Gordonstoun, a private school on the north coast of Scotland, Philip was tough, independent and able to fend for himself; he'd had to be. Gordonstoun would channel those traits into the school's distinct philosophy of community service, teamwork, responsibility and respect for the individual. And it sparked one of the great passions of Philip's life - his love of the sea.

Philip adored the school as much as his son Charles would despise it. Not just because the stress it put on physical as well as mental excellence - he was a great sportsman. But because of its ethos, laid down by its founder Kurt Hahn, an exile from Nazi Germany.

That ethos became a significant, perhaps the significant, part of the way that Philip believed life should be lived. It shines through the speeches he gave later in his life. "The essence of freedom," he would say in Ghana in 1958, "is discipline and self-control." The comforts of the post-war era, he told the British Schools Exploring Society a year earlier, may be important "but it is much more important that the human spirit should not be stifled by easy living". And two years before that, he spoke to the boys of Ipswich School of the moral as well as material imperatives of life, with the "importance of the individual" as the "guiding principle of our society".

And at Gordonstoun was born one of the great contradictions of Philip's fascinating life. The importance of the individual was what in Kurt Hahn's eyes differentiated Britain and liberal democracies from the kind of totalitarian dictatorship that he had fled. Philip put that centrality of the individual, and individual agency - the ability we have as humans to make our own moral and ethical decisions - at the heart of his philosophy.

And yet he was throughout his life, first in the navy and then in the many decades of life in the Palace, tightly bound by rules of tradition, of precedent, of command and hierarchy. He had little, if anything, in the way of agency. Did he say one thing and do another, as members of the Royal Family are often accused of? Or was his first choice - to serve - by necessity his last?

At Dartmouth Naval College in 1939, the two great passions of his life would collide. He had learned to sail at Gordonstoun; he would learn to lead at Dartmouth. And his driving desire to achieve, and to win, would shine through. Despite entering the college far later than most other cadets, he would graduate top of his class in 1940. In further training at Portsmouth, he gained the top grade in four out of five sections of the exam. He became one of the youngest first lieutenants in the Royal Navy.

The navy ran deep in his family. His maternal grandfather had been the First Sea Lord, the commander of the Royal Navy; his uncle, "Dickie" Mountbatten, had command of a destroyer while Philip was in training. In war, he showed not only bravery but guile. It was his natural milieu. "Prince Philip", wrote Gordonstoun headmaster Kurt Hahn admiringly, "will make his mark in any profession where he will have to prove himself in a trial of strength".

Others had their reservations about the brilliant and ambitious young officer. In peace, once he had his own command, he drove his men hard, much too hard for some. "If he had a fault, it was a tendency to intolerance," wrote one biographer. That kind of comment would recur. Contemporaries were more blunt. "One of his crew," writes another biographer, "said he would rather die than serve under him again."

In Dartmouth in 1939, as war became ever more certain, the navy was his destiny. He had fallen in love with the sea itself. "It is an extraordinary master or mistress," he would say later, "it has such extraordinary moods." But a rival to the sea would come.

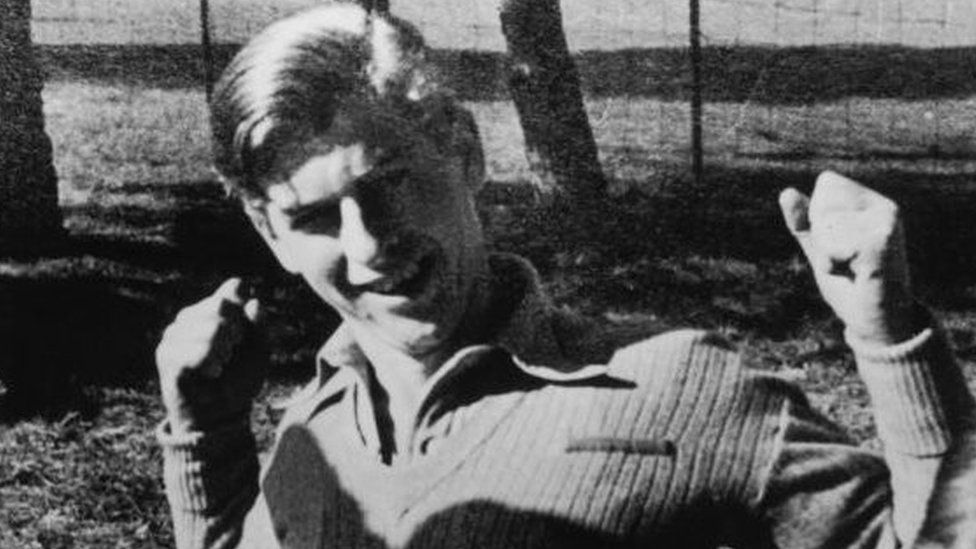

When King George VI toured the Naval College, accompanied by Philip's uncle, he brought with him his daughter, Princess Elizabeth. Philip was asked to look after her. He showed off to her, vaulting the nets of the tennis court in the grounds of the college. He was confident, outgoing, strikingly handsome, of royal blood if without a throne. She was beautiful, a little sheltered, a little serious, and very smitten by Philip.

Did he know then that this was a collision of two great passions? That he could not have the sea and the beautiful young woman? For a time after their wedding in 1948, he did have both. As young newlyweds in Malta, he had what he so prized - command of a ship - and they had two idyllic years together. But the illness and then early death of King George VI brought it all to an end.

He knew what it meant, the moment he was told. Up in a lodge in Kenya, touring Africa, with Princess Elizabeth in place of the King, Philip was told first of the monarch's death. He looked, said his equerry Mike Parker, "as if a tonne of bricks had fallen on him". For some time he sat, slumped in a chair, a newspaper covering his head and chest. His princess had become the Queen. His world had changed irrevocably.

For someone who almost never displayed anything close to self-pity, and rarely spoke of his own emotions, he was by his own standards candid about the loss of his naval calling. "There's never been 'if only'," he said once, "except perhaps that I regret not having been able to continue a career in the navy". Those who knew the man and his passions are blunter. The former First Sea Lord, Admiral Lord West, says Philip did his duty; but of the end of his time in the navy he says, "I know it was a huge loss to him. I know it."

That moment, when princess became Queen, revealed another great contradiction of Philip's life. He was born and brought up in a world almost entirely run by men. He was a rugged, physical man who was brought up and then worked in an entirely male environment. He celebrated masculinity, telling Mike Parker on the birth of his first son Charles, "It takes a man to have a boy." But literally overnight, and for 65 years to follow, it became his life to support his wife, the Queen.

He would walk behind her. He would give up his job for her. He would apologise if he came into a room after her. At her coronation he knelt before her, his hands enclosed by hers, and swore to be her "liege man of life and limb". His children would not bear his name, Mountbatten. "I'm nothing but a bloody amoeba," he exclaimed at that. But there was nothing to be done. She was the Queen. He was her husband.

Prince Philip talked of the upending of circumstance little. "Within the house," he said of the time before the Queen's accession, "I suppose I naturally filled the principal position. People used to come and ask me what to do. In 1952 the whole thing changed very, very considerably."

The transition to life in the Palace was brutal. "Philip," said his equerry, "was constantly being squashed, snubbed, ticked off, rapped over the knuckles... I felt Philip did not have any friends or helpers." Philip may not have helped himself; one biographer writes that in the early years Palace staff felt he was "difficult to deal with... prickly... arrogant... defensive". He was looked upon with suspicion by some in the court, as something of an adventurer, as perhaps a fortune hunter. He had German blood, and this was just after the herculean effort of defeating Nazi Germany.

In response, Philip began what would become a lifetime of near-ceaseless activity; abroad he was at the side of the Queen on the long tours they undertook, sometimes breaking off to pursue interests particular to him - sporting, industrial or research. She nearly always travelled with him as her companion; but he also travelled alone. It was he, not she, that made the farewells to colonial possessions in the 1950s and 1960s.

At home there were patronages and projects, hundreds upon hundreds of them, with a focus on youth, science, the outdoors and sport. He played cricket, squash, polo; he swam, sailed, rowed and rode horses and carriage drove. He learnt to fly, and developed his own photographs.

Within the Palace he was a moderniser, striding the corridors, rootling around the cellars, trying to find out what everyone did. He took over the management of the estate at Sandringham and over the years significantly redeveloped it.

"He believes he has a creative mission," wrote an early biographer, "to present the monarchy as a dynamic, involved and responsive institution that will address itself to some of the problems of contemporary British society."

He was young and very good looking; he smiled and joked and was at ease in front of the cameras. When he visited a boys' club in London in the late 1950s, a photo shows him with a broad smile on his face, looking crisp in a double-breasted pinstripe suit, his hair slicked back with brilliantine, surrounded by the upturned faces of boys and their mothers all shoving and trying to get close to him. There is more than a whiff of Beatlemania to the moment.

In his study on the first floor of Buckingham Palace, overlooking the gardens and Green Park, surrounded by thousands of books, with a model of his first command HMS Magpie to one side, he would research and write and type out his speeches. (In 1986 he would buy, always the moderniser, what he called a "splendid gadget" that he called "a miniature word processor".) He gave between 60 and 80 speeches every year, decade after decade, on topics that reflected his vast range of interests.

Out of the speeches comes a picture of the man. For someone who sat through so much of it, he was clearly impatient with ceremony. "A lot of time and energy," he told students and staff at the Chesterfield College of Technology, "has been spent on arranging for you to listen to me to take a long time to declare open a building which everyone knows is open already."

Reflecting his dizzying range of interests, there was sometimes a touch of the gentleman-farmer to his thoughts - well-organised arguments that don't really go anywhere, a lot of anecdotal evidence ("it seems to me...") garnered from his extensive travels.

Despite modernising instincts, he was a conservative, somewhat suspicious of the machinations of the big city. He spoke of "urban dwellers" and of the "average citizen" dumping rubbish from their car. He preferred practical solutions to highfalutin theory - "The enterprise is doomed," he told the Commonwealth Conference on Industrial Relations, "if it is allowed to enter the rarefied atmosphere of theory."

He was an environmentalist before anyone really knew what that was. He warned of the "greedy and senseless exploitation of nature." And in 1982 he brought up a topic that now grips us, but back then was almost never spoken of, "a hotly-debated issue directly attributable to the development of industry... the build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere," which he referred to as the "greenhouse effect".

And he constantly did himself down, shrugging as to why anyone should want to hear him speak: "I have very little experience of self-government," he told one audience, "I am one of the most governed people you could meet...." His example of irrational behaviour? - "making and listening to speeches on important occasions". Or speaking before the Brussels Expo in 1958 - "I feel I can claim to be an expert at going round exhibitions." He knew most speeches were a dull formality that had to be got through - and he was happy to let his audience have a laugh at his expense.

It is another contradiction in a life of them; that someone who cared so much about how we live our lives, about how to pursue a good and moral life, about how government and society might try to channel our instincts, should end up being popularly portrayed as a saloon-bar bore, his retirement from public life in 2017 accompanied by lists of his "gaffes", off-colour comments and salty jokes.

That he could be rude, startlingly so at times, there is no doubt. Part of it was impatience, that dynamo whirring away, the desire to get things done double-quick. Part of it may have been deafness, inherited from his almost wholly deaf mother. But part of it was just plain bad manners, a disregard for what others felt and a thoughtlessness that came from position and temperament.

There was for a long time a fair amount of barking and shouting at those who failed to please him, and not a lot of thanking those that did.

Looking back down the decades, two great contrasts stand out. The first, that between a life led in the public eye, and a really quite private man. The boy shuttling between guardians and schools and countries quickly learnt to seal off his private side from public view. Inside the Palace it became his world view. Most of his biographers' personal queries were met with a shrug, as if to say "I don't know why you are bothering". He once said of his son Charles: "He is a romantic, I am a pragmatist. And because I don't see things as a romantic would, I'm [perceived as] unfeeling." There can be little doubt that he was stung by the accusation. But his inner thoughts were not for public consumption.

And the second great, related, contrast is that between the near unceasing whirl of his public life, and a degree of solitude in his private. Of course there was family, though all his sisters pre-deceased him. But few, if any, great friendships are recorded, a corollary of his private nature and the pattern of his many decades. "Life," wrote one biographer, "hasn't enabled him to build up friendships. He is going round the world at such a lick." And royalty is its own curious cage, repelling outsiders. "What the royal family offers you is friendliness," said the late James Callaghan, prime minister in the 1970s, "not friendship."

Major General Charles Stickland of the Royal Marines, of which for 64 years Philip was Captain General, tells of when the duke flew into an exercise in Norway. He was supposed to say a quick hello to the enlisted men and then have lunch with the commanding officer. Instead he "asked two of the corporals to spoon food into his mess tin, sat on a Bergan [rucksack], told stories and chatted away with my troops when he was supposed to be having a posh lunch and then got back on the helicopter, having inspired a group of young men as to why it was great to be a Royal Marine".

It was vintage Philip; no ceremony, hierarchy pushed to one side, the big group over the more intimate gathering.

Because of his desire for privacy, because of his position, and because nearly all who knew him best have gone, our understanding of him will always be incomplete. But that's also because of what kind of person he was, because of the contradictions and contrasts that emerged over the decades. "A mercurial man like His Royal Highness," said the artist and architect Sir Hugh Casson, "needs a loose fit portrait."

He was asked once what his life had been about (the sort of question that normally received an incredulous snort). Had it been about supporting the Queen? "Absolutely, absolutely," he replied. He didn't see himself as a leader, though lead he could. And his own achievements he consistently played down. Accepting the Freedom of the City of London in 1948, he spoke for himself and for what he called other "followers", with trademark modesty. "Our only distinction," he said, "was that we did what we were told to do, to the very best of our ability, and kept on doing it."

Related Internet Links

April 09, 2021 at 11:15PM

By Jonny Dymond

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-50589065

Labels: BBC News

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home