: ‘I have these really deep beliefs about stability and survival’: Anna Sale, host of ‘Death, Sex and Money’ podcast, on our evolving relationship to money

What is money for?

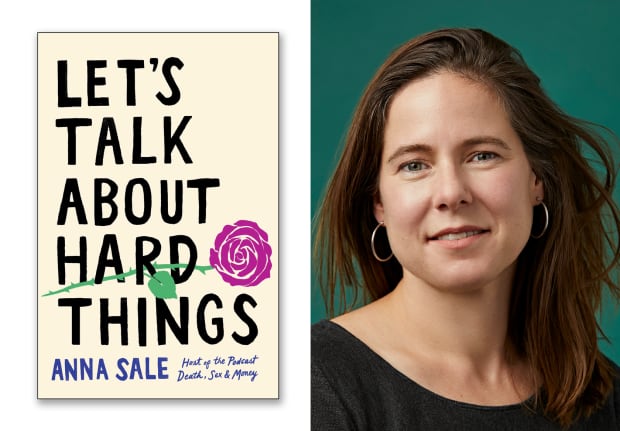

I recently found myself reflecting on this question after reading Anna Sale’s “Let’s Talk About Hard Things.” In the book, Sale, the host of the podcast Death, Sex and Money, writes that understanding our answer to this question can be critical to navigating finances in relationships. And yet, it’s one we rarely take the time to discuss out loud.

That’s a tendency Sale is pushing to change. In looking at just the last few months in my own life, it was easy to find evidence for her argument.

Recently when my husband and I were searching for an apartment in Philadelphia, a city where we’ve never lived before, we stumbled a bit in deciding on a budget and the type of apartment we were looking for.

It seemed obvious to me that we should upgrade from our current one bedroom in Jersey City. For one, we’ll be going from one income to two, given that my husband recently graduated from dental school. In addition, the cost of living is lower in Philadelphia, so we could afford something bigger and nicer for the same price as our current rent.

But my husband saw the move as an opportunity to save. If we can get the same as what we’re used to for significantly less, he reasoned, why not put the extra money away for a down payment, to pay off student loans or address another financial priority?

Our views on the apartment could really be boiled down to what we think money is for. I see it as a tool to provide comfort, which I define pretty broadly to include the stability that comes with paying the bills, saving for the future, and yes, the small joys that some material goods provide.

To my husband, the biggest benefit money can offer is security; he sees it as a tool “to sleep at night” as he puts it, and so watching our savings account grow would provide him with more happiness than a bigger space to live.

We ultimately agreed on a place, but next time we make a big money decision, I plan to take Sale’s advice to get clear about our priorities — and then focus on the cells in a spreadsheet.

The value in interrogating our beliefs surrounding money is just one of the many novel ways Sale suggests readers approach their finances and, in particular, conversations about them. We spoke about where personal-finance literature falls short, the importance of sharing your money story, and more.

The conversation has been edited and condensed.

MarketWatch: Long-time listener, first time caller! I don’t know if all of our readers are as familiar with your work as I am, so I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about how you came up with the idea for the book and how “Death, Sex and Money” influenced it?

Anna Sale: I started “Death, Sex and Money” back in 2014 because I found, it really came out of a place of personal need. At the time, I was divorced and in my early 30s and trying to make some really big decisions about my career priorities, and my relationship priorities, and I felt really alone in figuring that out.

I was drawn to hearing other people’s stories about how they had gotten through life transitions like this. I was asking people in my life to tell me about different moments, like when they were starting their careers, or when they were changing careers, or when they moved, or when they were starting a new marriage. I wanted to know all of it because I felt like I was in a dense forest without a guide. I wanted more stories just to understand that I wasn’t doing this on my own.

“ ‘I wanted to know all of it because I felt like I was in a dense forest without a guide.’ ”

The financial piece was really important to me. Before I started the show, I was covering politics, so something I covered a lot was Americans’ deep feelings about how our economy had changed to one in which they were in charge of more of the details. There has been this major long-time transition from being able to rely on the company pension to a gig economy, for example. With that enormous change in our economy, each of us has to figure out how to navigate our money in a different way, and specifically, in conversation.

I wanted to talk with people in my work about how they did money — I wanted to know if they had joint accounts in their marriages — or if they didn’t — or I wanted to know how they evaluated risks when they were trying to become an artist. In my personal life, I was hungry for concrete information. I wanted to know how people were figuring out living in expensive cities, how much savings was enough, and how they comforted themselves when they weren’t able to save and how they dealt with debt.

Those were all sorts of big questions that I wanted to dive into with the show. I started the book a few years after the show because I wanted to create more of a guidebook for myself and for readers about why to have these hard conversations and how to have these hard conversations in our personal life.

MW: One thing that really stood out to me in the book was the emphasis on acknowledging the different money circumstances we come from. Why do you think people are often hesitant to talk about that?

Sale: We have really mixed feelings and anxieties and shame about our financial histories no matter how we’re oriented. If you don’t have as much as you think you should, you feel bad about it, so you try to hide. If you have more than you think you should — or that you didn’t earn — then you feel bad about it, so you try to hide it. And polite society is telling us to just gloss over the details

My argument in the book is when you don’t share your money story as part of explaining your life story, there’s a lot that you’re papering over.

“ ‘When you don’t share your money story as part of explaining your life story, there’s a lot that you’re papering over. ‘ ”

Another reason why people don’t talk about money is because we have, in our politics, these very strict binaries of how we talk about money. Either you say people have what they have because of how hard they’ve worked, and how smart they are, and how talented they are and it’s all about individual achievement or individual fault. And then on the other side of the political spectrum, there are critiques of how systems are working and how structures are working, and less of an emphasis on individual agency.

Neither of those are wholly true, what is true and what is real is that each of us has what we have or doesn’t have what we don’t have as a result of factors that we are in control of and factors that we weren’t in control of. I decide how much money I’m going to spend on the things my family needs every week, and I also benefited from graduating into an economy that wasn’t in a recession when I was finishing college. I also benefited from being born into a family that didn’t have generational debt and so my parents were able to pay for my college education.

When you admit that where you are is the result of choices you’ve made and choices that you’ve had no control over, it’s a little easier to talk about money. In the absence of that conversation it’s so easy to go to the place and say, “Oh my gosh, how did everyone else figure it out and I haven’t?”

“ ‘Any extra money that we have I want to shovel it away into a savings account.’ ”

MW: One of my friends turned me on to this idea of what they call the “green check mark.” You’re wondering, how did they get this? If only they had a green check mark, like the blue one on Twitter, that let us all know how this happened.

Sale: Oh that’s interesting

MW: To your point, we could just talk more openly about it.

One of the questions that I loved to get at these conversations that was in the book is: “What is money for?” And I’m wondering if you can just talk a little bit about that question.

Sale: Asking what is money for — that gets at a whole other dimension of why money is hard. Because we don’t talk directly about money culturally, the beliefs and values that each of us carries around about money are often unspoken and unarticulated.

I didn’t analyze what I had been taught about money because it felt sort of natural, but in asking the question, “What is money for?” and having a conversation with my husband, Arthur, about it, it made me realize, oh, I have these really deep beliefs about stability and survival. Any extra money that we have I want to shovel it away into a savings account, and even money that we really should spend on things that we need, I still want to shovel it into a savings account.

“ ‘I have these beliefs about what is honorable as far as spending that is inherited from how I grew up.’ ”

I have these beliefs about what is honorable as far as spending that is inherited from how I grew up — and that is specific to the region I grew up in, the kind of family I grew up in, my family’s financial situation when I was growing up.

You might have another person, for example, a recent immigrant to the United States, who grew up in a family where everybody shares money and it’s all about this group of people instead of just thinking about individual achievement and individual stability. That’s a very different way of thinking about money that has really different consequences for how comfortable you feel lending and borrowing from people in your life.

If you don’t talk about it, you don’t realize that there is more than one way to do money. If you acknowledge that there’s more than one way to do money, then you’re all of the sudden in this conversation where you can say, “Huh, how do we want to do money?”

When you don’t have that conversation it feels like you’re going against this deep instinct and it made me anxious. Now I’m like, ‘Do I still believe these beliefs or do I want to make them a little more spacious?’ Because I now have words for them.

MW: One thing that I also really liked about the book is it’s offering money advice that’s different from your traditional personal finance literature. What do you think that literature gets wrong, and what are some healthier ways to use it?

Sale: I really love personal-finance literature, I’m not here to knock it. I have relied on personal-finance literature, and found it really useful in my life, I just think it’s not enough. The mistake that I can say I made and I think that is easy to make when you’re Googling financial questions is to race to the to-do list of what to do concretely with my money without examining: What do I believe about money? Or what else is at play here?

“ ‘What can happen in a hard conversation with someone in your life is you can add just a little more meat to the bone.’ ”

The other challenge with personal-finance literature is it can be really difficult to find advice that is full enough, context-wise, to contain all of the specificity and nuance in each of our lives. When you’re taking in personal-finance tips outside of a conversation, when you’re consuming tips on the internet, or a podcast, or tips in a magazine there’s a lot of one-size-fits all advice, like the certain percentages that you’re supposed to set aside for emergencies or retirement.

What can happen in a hard conversation with someone in your life is you can add just a little more meat to the bone, you can think about what need to be the sacrifices and accommodations in the short term in order for you to get to the long term.

MW: Have there been any conversations that really stand out in your mind either through “Death, Sex and Money,” or the book that made you change the way you think about money or change your approach to money?

Sale: What I have learned form doing the interviews on “Death, Sex and Money” and writing the book is that there is more than one way to do money the right way. I had this idea that I needed to follow the rules in order to be safe — that was my attitude about money growing up — and the thing is there aren’t rules that are going to keep you safe. There’s too much uncertainty to control for that.

There are particular life phases that you move through with money.

When I became a new parent and all of the sudden I had to pay for child care, I was so freaked out about it because it was this outlay of money, big constant weekly bills that I had never had before.

It really helped me to talk to other parents about what it was like for them when their kids were too young for public school. It just reminded me that it was something that was going to be a discrete period of time, instead of this bottomless pit of something screaming for more money, which is how I felt it emotionally.

The other thing that I have learned from doing the show and also, quite frankly, in my marriage is this trick of zooming into the numbers and then zooming out to what is our vision together? Let’s get clear about our priorities, and then let’s go to this question of how much should we spend on this rug in our living room.

June 12, 2021 at 02:26PM

Jillian Berman

http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story.asp?guid=%7B20C05575-04D4-B545-747A-2F640D977ACC%7D&siteid=rss&rss=1

Labels: Top Stories

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home