Rex Nutting: Here’s why higher prices for car rentals, airfares and computers won’t lead to higher inflation

The first ironclad rule of economics is that nobody likes paying higher prices. So it’s no wonder that people are getting nervous when the prices of some goods and services surge as the global economy emerges from the COVID-19 disruptions.

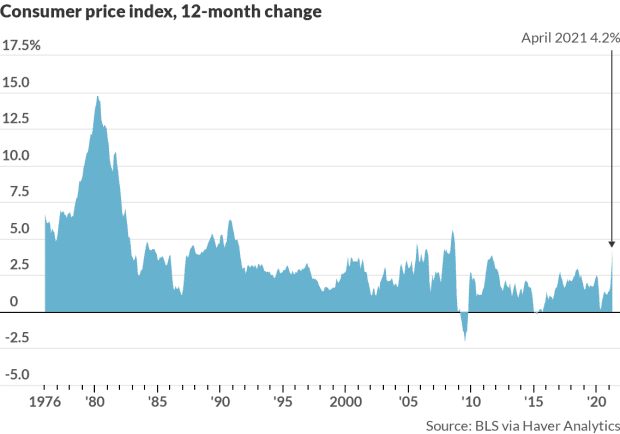

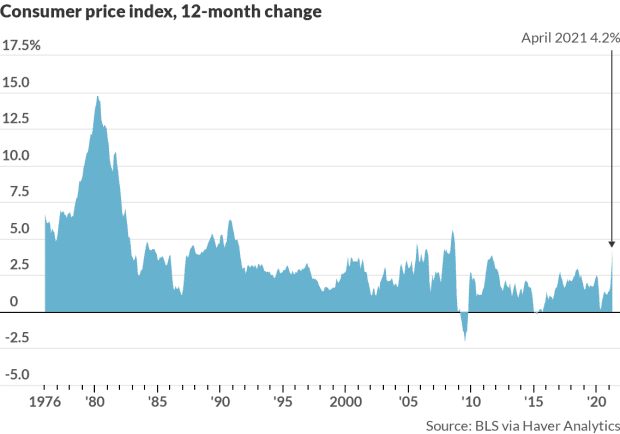

In April, the U.S. consumer price index rose 0.8% and grew 4.2% over the previous 12 months, the fastest rate since 2009. That sounds ominous, doesn’t it? The May CPI will be released on Thursday, with economists forecasting a 0.5% increase

Preview of Thursday’s report: The CPI was still surging in May, data likely to show.

But a closer look at which prices rose and which didn’t provides some comfort: Prices are mostly reacting to huge disruptions in supply and demand in particular markets, not to a general inflationary dynamic in most markets.

Higher inflation rates aren’t baked into the cake. Not yet.

The CPI is up 4.2% in the past year, but there are good reasons to believe that this is not the beginning of another round of hyperinflation such as we saw in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Relative price changes are not inflation

It may sound odd, but higher prices are not inflation per se. If the prices of used cars or computers or tickets to Saturday’s ballgame jumped because the demand rose faster than the supply, that’s not inflation. It’s just a relative price change, the kind of thing that happens continuously in dynamic market economies.

Menzie Chinn: Here’s how to tell if this spurt of inflation is here to stay

The second ironclad rule of economics is that prices matter a lot in a market economy.

Relative price changes are the main signal that buyers and sellers alike use to guide their economic behavior. If prices for vehicles, computers and many other durable goods are higher because semiconductors are in short supply, that sends a powerful signal to sellers to produce more chips, or to find alternative sources, or to find cheaper substitutes. They tell buyers to hold off buying if they can, or to find cheaper substitutes.

Or, if prices are lower because people aren’t leaving their homes due to health precautions, that’s a powerful signal to sellers to produce fewer full-service restaurant meals, baseball tickets and hair cuts, and to produce more takeout food, streaming entertainment content and do-it-yourself hair clippers.

With the help of price signals, supply and demand in those particular markets can quickly come to a new equilibrium.

Essential role of prices in market economy

It’s no exaggeration to say that prices are the essential mechanism that makes the market economy work. They are the market. Prices ebb and flow all the time in particular markets without stoking inflation or deflation in all markets. Policy makers notice these changing prices, but they don’t intervene unless they become so general and persistent that buyers and sellers begin to be guided by their expectations of future inflation (or deflation) in all markets instead of by conditions in their own market.

Harold James: Higher prices aren’t always a bad thing. Sometimes they nudge producers and consumers toward necessary changes

When we think about inflation or deflation, what we really want to know is what will happen to our purchasing power. Will our income be sufficient to purchase the same or a better standard of living next year or in 20 years? Will we be able to repay our debts? Will our investments appreciate faster than prices?

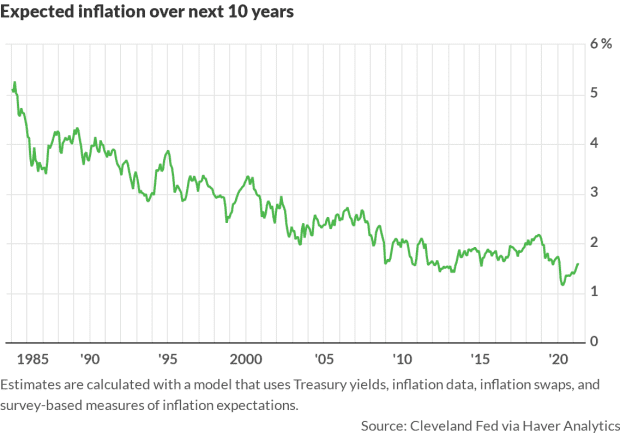

Fortunately, buyers and sellers don’t expect inflation to accelerate any time soon. The Cleveland Fed’s analysis shows the expected inflation rate over the next 10 years remains below 2%.

Longer term inflation expectations remain modest despite the recent surge in prices.

All the inflation data we have is backward looking. We know what prices were, but we don’t know what they will be. How can producers, consumers, investors and policy makers make decisions about the future without knowing what prices will be? That’s the destructive power of accelerating or decelerating inflation: It makes planning difficult, if not impossible.

Economists have developed a lot of tools to help them figure out if the price changes we experience are the ephemeral changes in particular markets that make the economy function or the lasting changes in all markets that erode purchasing power and confidence in the future.

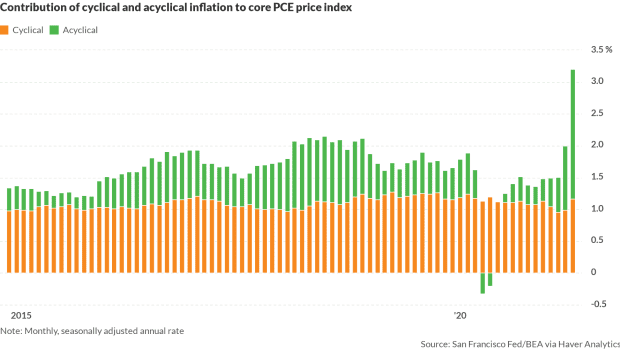

The orange bars show that the pace of underlying inflation has been fairly steady. The green bars indicate that most of the price increases seen over the past few months are due to supply-and-demand shocks in particular markets, not to an increase in inflationary dynamics.

The evidence

When Fed Chairman Jerome Powell says that the evidence indicates that the current jump in the CPI will likely be “transitory,” he’s referring to these tools.

Because inflation is a general increase in the price of almost everything, one tool we can use to decipher the underlying inflation rate is to strip out all the items with large price changes, either up or down, on the assumption that most of these are one-off reactions to supply or demand shocks (including technological change).

This allows us to see what’s happening to the average price level. The Cleveland Fed produces a trimmed-mean price index for the CPI, and the Dallas Fed produces a trimmed mean index for the personal consumption expenditure price index (which is the inflation measurement the Fed prefers because its coverage is broader).

When the April CPI came out, we all heard that the price for a rented car or truck had soared 16.2%, that airfares jumped 10.2%, and that admissions to sporting events leapt 10.1%. But we didn’t hear that the price of fuel oil dropped 3.2%, or that computer software prices fell 1.9% or that potato prices sank 1.8%.

And we didn’t hear that the Cleveland Fed’s trimmed-mean CPI showed an underlying inflation rate of 2.4% over the past year, exactly the same as it was in February 2020 when the pandemic hit. That’s a clear sign that inflation isn’t taking off.

The Dallas Fed trimmed mean showed the same thing.

‘Sticky’ prices

Another method to parse what’s really going on is to look at what’s happening to “sticky” prices (which don’t fluctuate frequently), such as rents or insurance premiums. Accelerating increases in these prices indicate that buyers and sellers in these markets expect higher inflation.

A similar technique invented by researchers at the San Francisco Fed divides the market basket into two buckets: cyclical prices that rise or fall as the economy expands or contracts, and acyclical prices that mostly react to what’s happening in a particular industry or sector.

Almost all of the acceleration in prices in March and April was due to acyclical price increases due to peculiar factors in specific sectors, not to a rise in underlying inflation.

For the Fed and other policy makers, this matters. Monetary and fiscal policy can affect the cyclical inflation (about 42% of the PCE market basket), but it can’t do much in the short run about the idiosyncratic forces that influence prices in the other 58% of the consumer economy.

If this is the right way of looking at inflation, the current bump in inflation should be short-lived as the bottlenecks, supply constraints and pent-up demand are worked out in each industrial sector.

Most likely, the pandemic, the sharp recession and the rapid recovery have not significantly changed the inflationary dynamics of the economy. Gripe all you want about the price of a rented car (if you can find one), but don’t expect these price pressures to persist.

More on inflation

Andrew Keshner: Brace yourself for a summer of shortages—from lifeguards and fireworks to lobster and beef burgers

Mark Hulbert: Is inflation going higher or lower? We checked with the model that has the best record

Joseph Stiglitz: The fear of inflation is a red herring designed to distract us from the need for policies to reduce inequality

June 10, 2021 at 10:59AM

Rex Nutting

http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story.asp?guid=%7B20C05575-04D4-B545-7495-3B6D1999969E%7D&siteid=rss&rss=1

Labels: Top Stories

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home