: Teen jobless rate falls to lowest point in years

The latest jobs report might have been so-so, but at least the kids are alright.

The unemployment rate in May for 16- to 19-year-old workers dropped to 9.6% from 12.3% a month earlier.

If that doesn’t sound striking — especially when the overall jobless rate encompassing teens and adults is now a pandemic-low 5.8% — here’s some context:

The rate handily beats the 29.6% unemployment rate for the demographic at the same point last year, when the country was first reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The current rate is also lower than the 12.3% jobless rate for the demographic in May 2019. As of last month, 33.2% of the 16- to 19-year-old population had a job, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In May 2019, it was 30.2%, BLS numbers showed.

The May unemployment rate for Black teens was 12.1%, which Dean Baker, senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, pointed out was “lowest on record.”

Actually, you have to go back to November 1953 to find a lower jobless rate for all teens, when it was 8.6%.

Of course, different measures show more recent periods of positive jobs numbers for teens. For example, in May 2008, 34.1% of teens were employed and the teen labor force participation rate — which counts the rate of people who have a job or are looking — was also larger than now.

Still, “the rebound has been really good for them,” said Paul Harrington, a Drexel University professor who has studied teen employment trends.

When the pandemic first hit, teen workers were clobbered with pink slips. Now, the low rate is “good for teens, it’s good for the economy, it’s good for America,” Harrington said.

So what’s going on?

A mix of factors are at play, Harrington and other experts said.

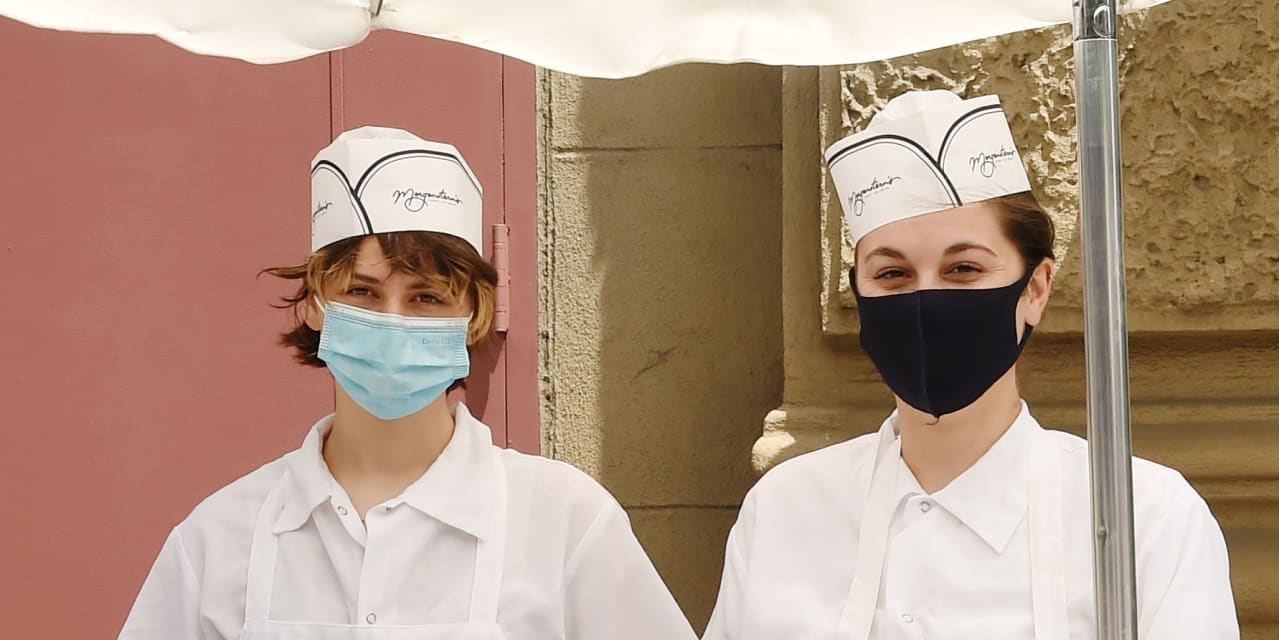

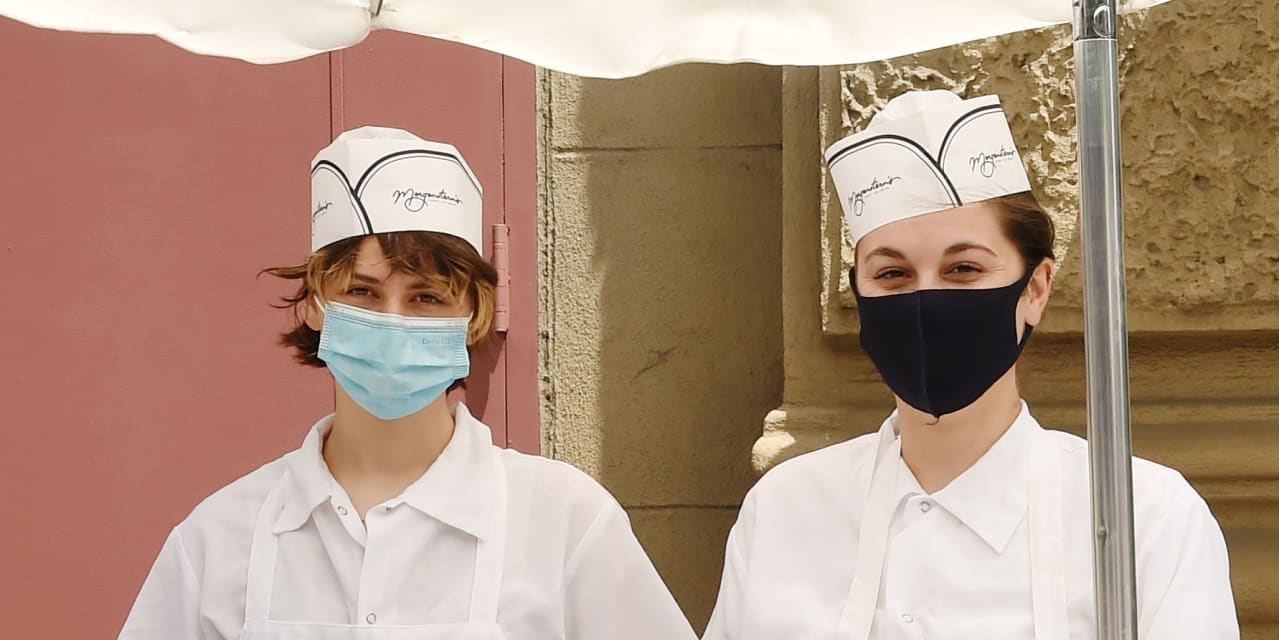

For starters, summer is nearing and that’s the time teens traditionally pick up jobs. Nearly half of the teen workforce finds jobs in the leisure and hospitality business, Harrington noted. Think amusement parks, restaurants, fast food joints, ice cream stands, hotels and tourist-related work.

During May, leisure and hospitality accounted for 292,000 of the 559,000 jobs added to the economy as pandemic restrictions eased, BLS said.

But employers are also grappling with a labor shortage and economists debate how much of that has to do with factors such as generous unemployment benefits and the lack of child care options that keep would-be workers home.

Teens may be stepping in to fill a gap ordinarily filled by older workers. Employers in sectors such as hospitality “might be reaching out to workers that are more readily available, including teens, right now,” said Daniel Zhao, senior economist at Glassdoor.

Some companies are really trying to sweeten the deal now. For example, the convenience store chain Wawa is dangling a $125 signing bonus in its bid to hire 5,000 new workers between March and June. “Wawa is one of the places that always hired kids,” Harrington said. (Wawa did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

After a sharp tumble during the Great Recession, teen employment was bouncing back slightly in recent years, Pew Research Center data showed.

But before the pandemic, teens were increasingly competing with older workers for jobs, Harrington noted. “The older worker between 2000 and 2020 really penetrated the teen labor market.” Older workers, running a greater risk to COVID-19 exposure even with rising vaccination rates, might be thinking hard about returning to those roles, he said.

The pandemic is accelerating retirement plans for some in the Baby Boomer segment, Pew Research Center polling suggests.

Long term effects?

The lower teen unemployment rate is “not unequivocally great news,” said Elise Gould, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute.

For one thing, the amount of people in this group seeking work actually slipped slightly from April to May. Some job seekers might not be seeing opportunities and leaving the workforce altogether, she said.

If young job seekers put off education or drop out of school to land a job, Zhao said the move could, in all likelihood, hurt them in the long run.

But if it’s a job that doesn’t sacrifice education, then Zhao sees the spurt as a good thing. “Getting more work experience early on can be a powerful leg up,” he said.

Harrington likes what he sees because summer jobs are important first lessons about finances and career steps as teen workers grow up.

“They develop savvy or how the market works, because you’re actually in a market,” he said, later adding, “The more kids, the merrier.”

June 06, 2021 at 03:08PM

Andrew Keshner

http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story.asp?guid=%7B20C05575-04D4-B545-7482-D157BE45EF00%7D&siteid=rss&rss=1

Labels: Top Stories

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home